From Gilead to Bousbir

Part of an ongoing development journal for The Ogress of Fez, a feature drama about Oum El Hassen and the intersecting forces of empire, gender, and violence. Learn more.

I want to tell you a little about something I’ve been working on for the last few years.

It’s a screenplay, tentatively titled The Ogress of Fez, centred on an enigmatic figure called Oum El Hassen - a woman who lived in Morocco in the 1930s, during the period of French colonial rule. If her name appears at all today, it’s usually briefly, a passing reference in an academic text, or a footnote that doesn’t invite much attention.

In her own time, however, she became the subject of intense public attention. News of her crimes travelled far beyond Morocco, carried across continents by newspapers hungry for sensation. Oum was reduced to a figure rendered monstrous through embellishment and mythology, dubbed “the Ogress of Fez,” her story absorbed into a language of excess that blurred reportage with fantasy.

Oum was an Algerian-born woman who worked as a prostitute from a young age and later became a madame, running brothels along French military routes. She cultivated relationships with officers, acted as an informant, and for a time moved under the protection that proximity to power afforded.

What shattered that protection was the discovery of what had been taking place in her brothel in Meknes. Many of the women who lived and worked under her authority had been murdered. Reports describe killings involving strangulation and poisoning; bodies that were dismembered; women buried alive within the walls of the house itself.

The trial that followed was seized upon with extraordinary fervour. Newspapers across continents fed on the case, oscillating between horror and fascination, wrapping the proceedings in myth and moral panic. Oum was no longer a woman operating within a system, but a figure onto which fear and fantasy were projected.

Oum El Hassen bent Ali (known as Moulay Hassen), Nov. 17, 1938, Fez, Morocco, escorted by police before the courthouse (French Presse).

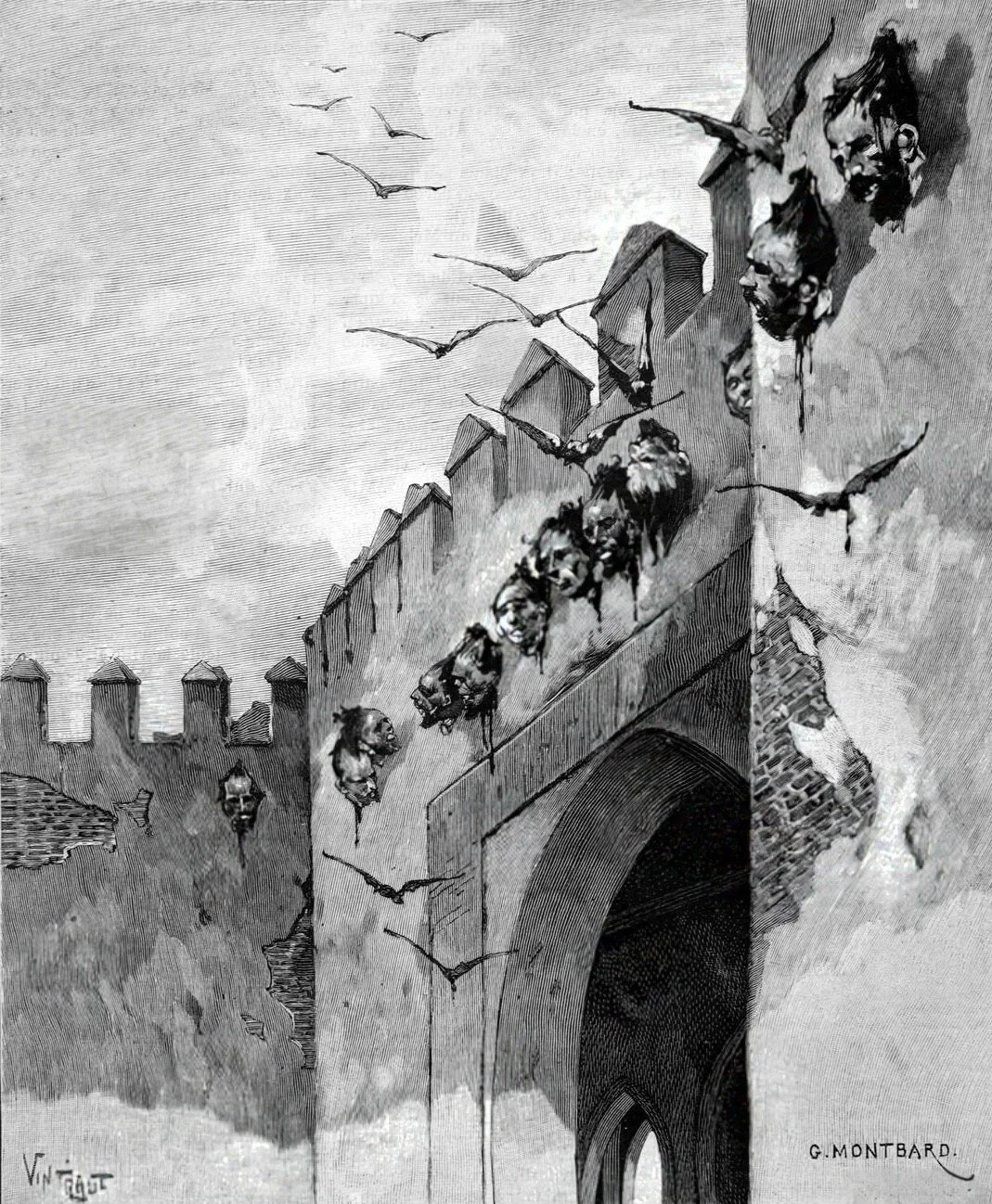

Oum’s crimes were brutal and shocking. But what is unsettling, in a different way, is the world in which they were exposed. This was a colonial world already saturated with violence. In Fez, only a few years earlier, the severed heads of rebels were displayed outside the city walls - photographed, circulated, even turned into postcards. These images moved freely through the colonial imagination, presented as evidence of order restored and authority reasserted.

As Susan Sontag reminds us, photographs do not simply record violence; they organise how it is seen, remembered, and absorbed. Here, the image does not shock so much as instruct - teaching viewers what power looks like, and upon whom it may be exercised.

Violence, in other words, was neither hidden nor exceptional. It was visible, aestheticised, and authorised - so long as it flowed in the right direction. What Oum’s case ruptured was a boundary around who was permitted to enact violence, and how it could be seen, rather than a taboo against killing itself.

What is impossible to ignore, beyond the violence of the case, is the way this story sits inside a much larger system, one that shaped Oum’s life long before she entered the record, and continued long after she disappeared from view.

Illustration depicting the display of severed heads on the walls of Fez following the suppression of resistance (circa 1911–1912). Photographs and postcards exist, but are not reproduced here.

Oum’s story haunts me, partly because it resists resolution, but also because I feel drawn to characters whose choices feel inevitable within their contexts, and to the uncomfortable question her story raises: what any of us might do under the same conditions.

When thinking about Oum, my mind has often returned to Aileen Wuornos, a woman whose crimes and trial became a media spectacle, particularly the moment in Nick Broomfield’s documentary, Aileen: Life and Death of a Serial Killer (1992), when her flat composure fractures into incandescent rage. That eruption touched me… and chilled me. It seemed to carry the weight of a thousand unspoken injustices. Behind it, I saw grief: the grief of what might have been had her life not been shaped by a litany of abuse, neglect, and cruelty. I saw in her not the monster as she had been labelled by the media, but a woman whose humanity had been eroded by a malignant and indifferent world.

I also recognise something of that erosion in Oum, as a way of understanding how a life is shaped - and misshaped - within a world where violence and hierarchy were daily lessons in who mattered and who did not.. But where Wuornos turned her violence outward, toward the men who exploited her, Oum’s violence moved in a different direction - towards the women in her care, women whose lives, in many respects, mirrored her own. That inversion is what makes Oum’s story so difficult to grapple with. It forces us to confront not only brutality, but complicity, and the ways systems of domination can turn survival into betrayal.

Aileen Wuornos. Photo by James Quine - Marion County Courthouse, March 31, 1992.

As I followed the structures that surrounded Oum, I found myself pulled deeper into the architecture of colonial prostitution: the regulated brothels, the medical inspections, the language of hygiene and order used to justify the control of women’s bodies under empire. Taken together, these mechanisms marked a shift from spectacular punishment to regulated surveillance, where power no longer needed to display itself because it had been absorbed into daily life, and therefore internalised.

Tracing these systems also meant confronting the limits of the archive itself - what has been preserved, what remains inaccessible, and what appears only in fragments. Much of this history exists behind institutional barriers, scattered across police files, medical records, and administrative correspondence that are difficult to access, if not actively hidden from view. Scholars such as Christelle Taraud have shown just how much is there, waiting to be read, even if it has not yet fully surfaced.

What becomes clear is that while systems of power can be mapped, the lives caught within them often cannot. The archive preserves structure more faithfully than it preserves experience.

As I moved deeper into the research, what had initially felt like historical distance began to collapse. It became clear to me that the archive does not lie dormant. It remains unsettled by what it cannot contain, as if something long inert still carries a faint pulse. Like roots slowly pushing through concrete, the past makes itself felt.

It was against this backdrop that I returned to Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale. Gilead was never imagined as a reflection of any single historical place. Atwood was writing speculative fiction rooted in the United States, drawing on theocratic traditions and real histories of authoritarian control rather than a specific past. And yet, rereading the novel and revisiting its screen adaptations, I was struck by how close it feels - emotionally, certainly, but also in the histories it brings to the surface.

It feels like something we have already witnessed… systems that weaponise the female body through surveillance, regulation, and force.

Gilead is not only an imaged place, it is in many ways a memory. It recalls the real-world systems that have shaped and controlled women’s bodies, especially under empire - systems practiced, codified and aestheticised in places like colonial Morocco.

One of them was called Bousbir.

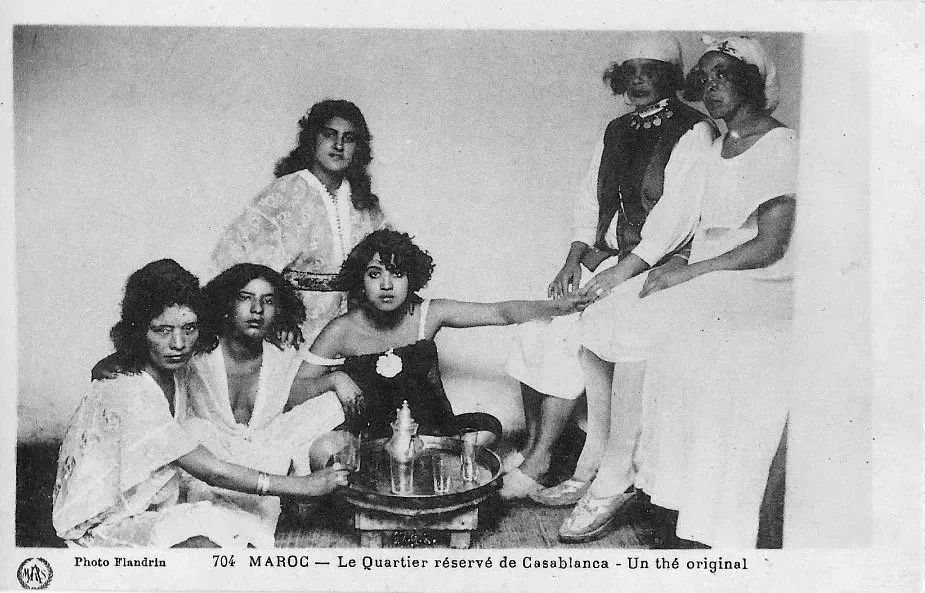

An image from a postcard of the Bousbir quarter, located in Casablanca.

Built in 1923 by the French colonial administration in Casablanca, Bousbir was a walled-off red-light district designed to house and regulate the sexual labour of Moroccan women. It was not an underground operation or a moral aberration, rather it was sanctioned planned, and legal. The women who lived there were not free.

They were confined.

Renamed.

Medically inspected.

Photographed.

Taxed.

Many were recruited under the guise of work, others coerced. Most came from poverty. Once inside, their bodies were rendered public property, structured for consumption and state control.

The French described Bousbir as a hygienic solution, a moral containment strategy to protect soldiers and settlers from disease and disorder. But Christelle Taraud’s research makes clear what this “hygiene” actually meant.

Women underwent weekly genital inspections, which were often invasive and public. The clinic rooms were lined with stirrups, women sat barefoot on mats, waiting their turn. The process was swift, clinical, and humiliating. They were sorted, treated if necessary, and returned to their rooms.

There was no consent.

The system didn’t require it.

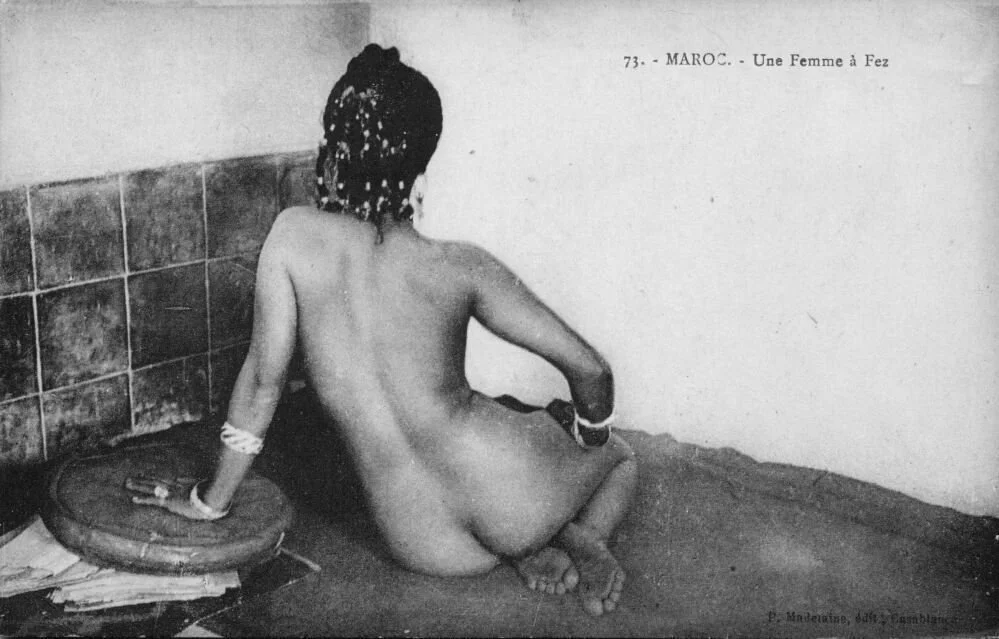

Photograph from Hygiène, médecine et chirurgie au Maroc (1937). Moroccan women subjected to colonial medical inspection.

Photographs taken during these inspections, many of which appear in the 1937 volume Hygiène, médecine et chirurgie au Maroc, show women mid-examination, partially clothed, surrounded by white-coated medical staff. Some turn away from the camera. Others hide their faces. The rooms are bright. The beds aligned. The uniforms spotless.

And yet the images themselves are violent.

Susan Sontag wrote that “to photograph is to appropriate the thing photographed.” In Bousbir, photography did more than appropriate. It transformed the women into colonial commodities: postcards, trophies, evidence of imperial progress.

In The Handmaid’s Tale, the Commanders justify their actions with religious language and appeals to duty. In the colonial archive, administrators write of security, order, cleanliness. The tone is always measured. The violence is always procedural, embedded in routines, schedules, and architecture. Atwood’s dystopia is unsettling precisely because it feels designed, tested, and entirely rational - at least to those who built it.

This is what I find so chilling in both Gilead and Bousbir: the violence, and the calm that normalises it.

The bureaucracy.

The logic.

The ritual.

Still from The Handmaid’s Tale. A handmaid’s body monitored under state control.

Foucault described this as “biopower”; the management of life by the state through the control of bodies, reproduction, and public health, rather than through an overt threat. In both Gilead and Bousbir, women’s lives are regulated by ideology as well as institutional routines. Surveillance becomes a system of recording and valuation. Who is clean? Who is fertile? Who is obedient? The medical file replaces confession, and the clinic becomes a kind of confessional booth with specula instead of sacraments.

Colonial brothel infirmary in Morocco, where women were forced to undergo weekly medical checks.

I keep thinking about how the women in Bousbir were photographed as objects of a colonial fantasy. The ideal “Mauresque”, beautiful, passive, veiled but available. Orientalism packaged as science. Sexual control masquerading as social reform.

French colonial postcard titled “Une femme à Fez.” One of many eroticised images produced and circulated to satisfy European fantasies of North African women.

In Gilead, there is a similar erasure of individuality. Handmaids wear identical robes. They greet each other with the same prescribed phrases: “Blessed be the fruit.” “May the Lord open.” Their identities are overwritten by the roles they are forced to play. They become vessels, symbols, signs. They are visible, but not seen. They are named, but not known.

Still from The Handmaid’s Tale.

What links these systems is not only the management of women’s bodies, but the systematic removal of their subjectivity. Women are not meant to narrate their own experience.

In The Handmaid’s Tale, that silence is broken by June’s voiceover - narration as testimony, spoken from inside the very system that seeks to erase her. It is an act of resistance, not a permission. In Bousbir, no such voices remain. The archive is built from the outside: doctors, officials, photographers. It is a structure of absence.

As Saidiya Hartman asks, how can we revisit these scenes of subjection without replicating the violence that silenced them in the first place?

What continues to haunt me, and shapes the emotional core of The Ogress of Fez, more than the violence itself, is the ease with which it was rendered reasonable - spoken as care, necessity, and public good..

In Bousbir, the weekly inspections were photographed as orderly and scientific. There is even a sense of choreography to the images. But this performance concealed something far more brutal. The forced genital examinations, carried out with little or no privacy, were deeply violating. And yet in the visual record, they are rendered sterile, almost serene.

Something similar is staged in Gilead. The ceremonies are highly ritualised and symbolic, performing in matching outfits, on manicured lawns or candlelit parlours. The symbolism functions to legitimise cruelty, to cloak domination in reverence. Everything is designed to look respectable.

Still from The Handmaid’s Tale. Ritualised sexual violence (The Ceremony) in Gilead.

Taraud describes Bousbir as a theatre of colonial order. Its architecture mimicked a medina, an Orientalist fantasy constructed by French architects. Tourists were invited in. Postcards were sold. Photographers like Marcelin Flandrin posed women in so-called “traditional” dress, arranged and lit them carefully. The images often appear in books and archives today, often stripped of context, mistaken for neutral glimpses of culture.

Women in Bousbir, the colonial red-light district of Casablanca, photographed for a French postcard.

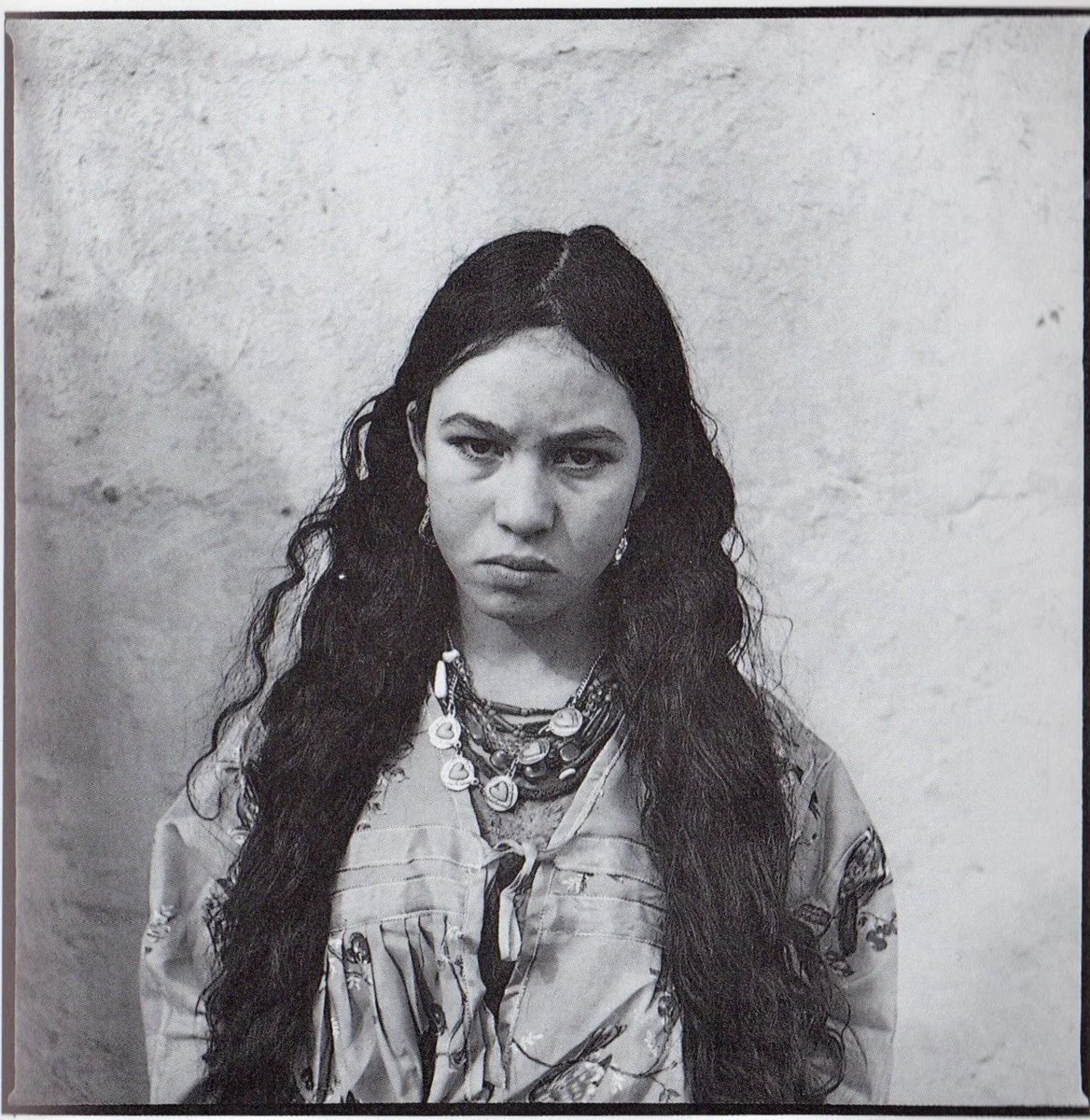

One photograph from the colonial medical archive shows a woman in stirrups mid-examination.But in the foreground, another woman looks directly at the camera. Her expression is closed, almost confrontational. There is no consent in that look. No complicity.

She seems to say: I see you.

Photograph from Hygiène, médecine et chirurgie au Maroc (1937). Moroccan women subjected to colonial medical inspection.

That is the gesture I want to hold onto. In systems built to erase subjectivity, even small refusals matter. Averted eyes. Folded arms. A name remembered. A story passed on in fragments.

Taraud calls this “violent negotiation”. The women of Bousbir were constrained, but not absent. Their subjectivity flickers at the edges of the record, in posture, in expression, in the decision not to smile before the shutter clicks.

Identification photograph of an Algerian woman under French colonial rule. Marc Garanger, 1960.

And this idea of the flicker - the trace of resistance inside the machinery of power - feels essential to the project I’m writing. The Ogress of Fez is not a historical film in the conventional sense. It’s fragmented and sensory, made of glimpses and interruptions.

What stays with me most from all this research, and from returning again to The Handmaid’s Tale, beyond violence that is both implicit and explicit in these systems, is the silence they produce - the way the historical record fails to hold the texture of a life, the tone of her voice, the detail of resistance.

Bousbir, for all its documentation, is a place of erasure. There are maps, medical files, financial records, photographs. The archive is full. But it is full of other people speaking: doctors, photographers, colonial officials.

What we don’t have is what the women thought of their lives.

We don’t know how they endured, or what they said to each other.

What they feared, what they hoped for.

We have only fragments, mediated through the lens of power.

Hartman calls this “the violence of the archive”, the way that such omissions from the record becomes part of the domination. She offers the idea of “critical fabulation” as a way of imagining into the gaps, writing with, not over, the silence.

That idea sits at the centre of The Ogress of Fez. I am not trying to reconstruct Bousbir as it was. I am trying to listen to its edges. To what resists translation. To the emotional weight of what’s missing.

I find myself returning, at this point, to Oum herself, as a figure who resists explanation. The archive gives us her crimes, her notoriety, her name reduced to a headline - the ogress of Fez. What it does not give us is how it felt to inhabit her position: to exercise power that was always borrowed, conditional, and liable to vanish at any moment.

Oum was neither outside the system nor fully protected by it. She enforced its rules while being shaped by them, benefitted from its hierarchies while remaining expendable within them. That tension, between authority and precarity, is what makes her so difficult to place, and so difficult to let go of.

I’m less interested in attempting to redeem or condemn Oum. I return to her because she embodies the contradictions of the world that produced her, a world that demanded complicity as a condition of survival, and then punished it as monstrosity.

Oum El Hassen at her trial in Fez. French Protectorate period (1931).

Sometimes I wonder what it means for me to be telling this story at all. I am not a woman. I did not live through Bousbir. But I am connected to Morocco, and to a lineage of women whose stories I only partly know - women who migrated, who disappeared, who were spoken about in half-sentences, whose names shifted in the telling.

There is an unease in that inheritance. This film, in many ways, is a way of sitting with that discomfort. Not resolving it, but staying inside it long enough to understand its shape.

In The Handmaid’s Tale, June’s voiceover breaks the silence of her world - testimony from within the very system that seeks to erase her. In the colonial archive of Bousbir, that kind of interior speech simply doesn’t survive. There may have been countless narrators, but their speech wasn’t preserved. What remains are the walls, the routines, the photographs, and the silences between them.

What I’m learning, slowly, is that silence is not the same as absence. That what can’t be fully recovered can still be felt. That the act of imagining, carefully and with humility, is a way of engaging with loss without pretending it can ever be reconciled or resolved.

A breath.

A refusal.

A word unsaid.

The Ogress of Fez is my way of returning to those rooms. To feel what it meant to live through it. To remember that even in the most controlled environments, even under inspection, even under His eye, there is still something that escapes.

Sometimes it’s just a gesture. A face turned away from the lens. A story told in secret. A robe left slightly unbuttoned. A woman who sees, but does not speak.

Not to recover the past, but to work with what survives of it.