Radical Realism

Part of an ongoing development journal for The Ogress of Fez, a feature drama about Oum El Hassen and the intersecting forces of empire, gender, and violence. Learn more.

I don’t want to see acting anymore.

I don’t care how “good” it is, how convincing the tears are, how finely calibrated the emotional beats. If I can see the seams of the performance, something in me recoils. I switch off. My body knows the difference. My gut knows the difference.

What I’m after is something far riskier, and much harder to pull off. I want to make drama that doesn’t feel like drama. I want to make fiction that bleeds into documentary, where the audience isn’t sure what they’re watching, only that it feels uncomfortably, devastatingly real.

Madonna in Dangerous Game (dir. Abel Ferrara, 1993)

A few films have done this for me. One, oddly, is Dangerous Game by Abel Ferrara. A messy, jagged film, often brutal, often excessive, but there’s a moment with Madonna that has stayed with me for years.

Madonna, playing the role of Sarah, sits under the verbal assault of Harvey Keitel’s character, who, as the director within the film, begins to unravel the boundaries of the film-within-a-film, the fiction they’re constructing, and reality itself. At one point, he calls her a “commercial piece of shit.” The insult lands hard, too hard. It doesn’t feel like something aimed at the character. It feels aimed at her. Madonna. The pop icon. The woman.

And in that moment, you see her freeze with a kind of stunned, wounded confusion. You can feel her calculating, Are we still in character? Is this still the scene? The line between Madonna and Sarah disappears, and what’s left is just a woman sitting in a room, being humiliated, and unsure if the cameras are still rolling.

That confusion, that emotional whiplash, is where the film becomes something else. Uncomfortable, yes. Maybe even indefensible. But cinematically, it’s electrifying. You’re no longer watching a performance. You’re witnessing a breakdown of structure, of safety, of distance. And for a few unbearable seconds, something real floods the screen.

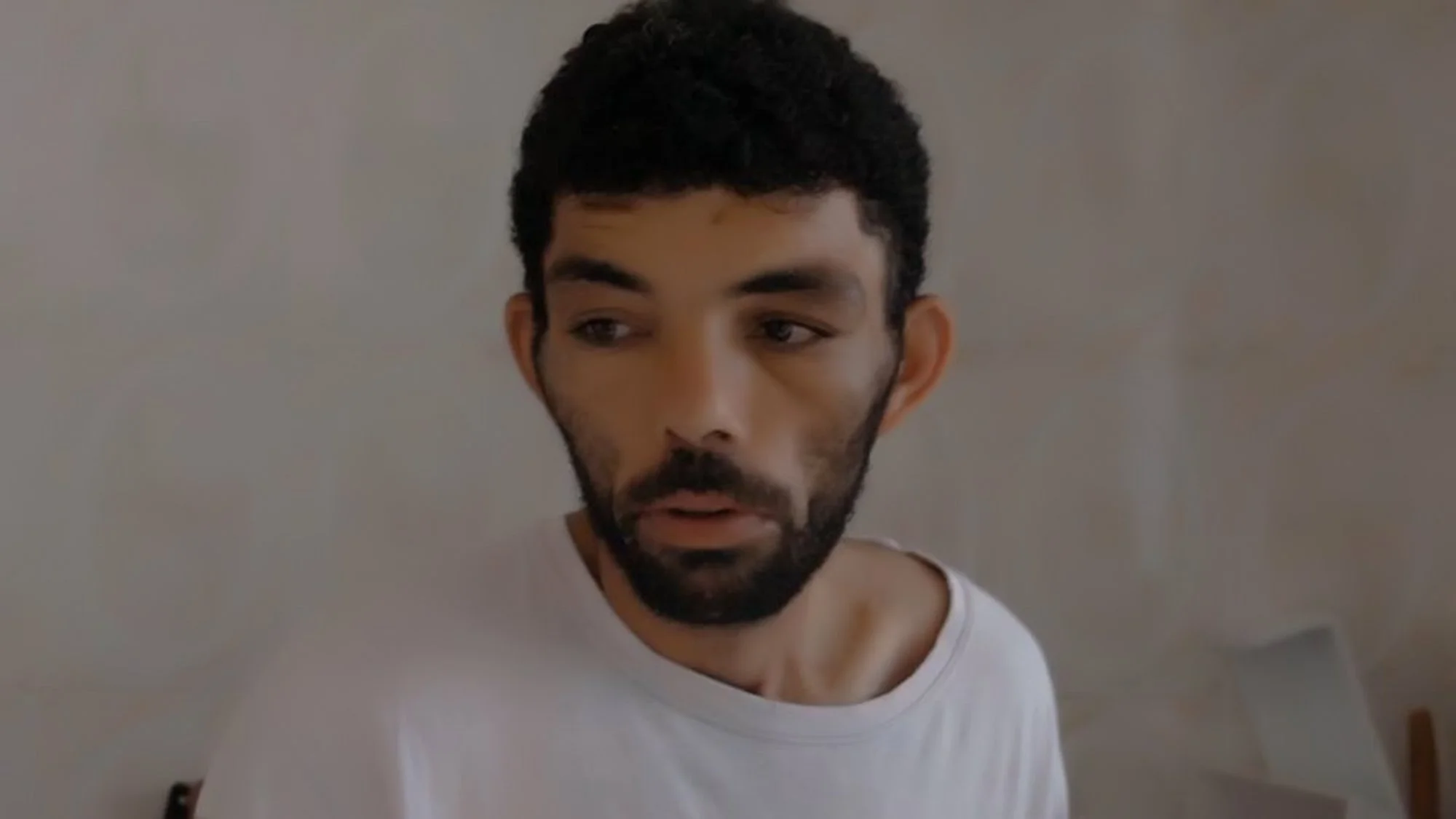

Fanta in Subutex (dir. Nasreddine Shili, 2018)

I felt the same watching a Tunisian documentary recently called Subutex. Two men on the edge of society, addicts, wanderers, philosophers in their own strange way, filmed with such intimacy that I kept asking, How did the director do this? How did they get this close? How did they shape something that felt so spontaneous and private, and yet had the clarity and rhythm of a narrative? I couldn’t tell where real life ended and storytelling began. That confusion is the highest compliment I can give.

There is a moment in Subutex that, like the scene with Madonna, crosses a line. Rzouga lashes out at Fanta. The violence is sudden, shocking, and the camera doesn’t flinch. It holds. There is no cut, no relief. The viewer is left inside the space, inside the moment, inside a room where something irreversible is happening.

And again, I found myself asking, What are we watching? Is this still a documentary? If it is, what is the filmmaker’s role when harm unfolds on camera? What is our role as spectators? The film does not intervene. It does not apologise. It does not explain. It holds the moment in silence and stillness, and lets us feel the weight of our position… watching, doing nothing.

The camera becomes a witness. Maybe even an accomplice. And in that space, the boundaries collapse. We are no longer viewing a documentary about addiction or marginality. We are inside it. The hammam is not a set. It is a world. A contained, humid, broken world in which survival is unpredictable and love and violence sit too close together.

That feeling - that we have entered someone else’s world entirely - is what stays with me. It is what I want for The Ogress of Fez. A film that feels like we have been granted access to something private and unrepeatable. Not because it is shocking, or even dramatic, but because it is unguarded. Because the people we are watching are not performing. They are present.

This is what I mean when I talk about radical realism. Not kitchen-sink realism. Not tasteful restraint. I mean moments that feel like breaches. Where we catch someone being, rather than acting. Where emotion isn't packaged, but leaks out unexpectedly. It’s something I’ve glimpsed in the Dardenne brothers’ work, the handheld closeness of Rosetta or The Son, where the body is always slightly ahead of the plot. Or in the haunted, unspoken pain of Pedro Costa’s Vitalina Varela, where stillness holds the weight of a thousand lives. Or in The Rider by Chloé Zhao, which uses non-actors inhabiting their own stories, allowing us to witness something irreducibly real.

That’s the place I want to reach with The Ogress of Fez. I don’t want actors pretending to be sex workers or colonial subjects or haunted women. I want people who know these worlds, in their bones. I want to create space for truth to emerge, fragile, unscripted, maybe even incoherent at times. I want real voices, unfiltered speech, gestures that aren’t blocked or choreographed but lived. I want to blur the line between testimony and fiction, not to deceive, but to deepen the experience of witnessing.

This means thinking differently. It means not casting in the usual way. It means building relationships, not just roles. It means showing up without a script, without answers, and trusting what arises. It means shooting rehearsals, moments between takes, and maybe keeping the camera rolling when everyone thinks the scene is over. It means rethinking what directing even is. Maybe it’s more about listening. Making people feel safe enough to be vulnerable. Letting the mask drop.

Of course, there are risks. Ethical risks. When does intimacy become exposure? What does consent look like when emotions shift inside a frame? What do we owe the people who open themselves up on camera? These are questions I’m still wrestling with, and maybe I’ll keep wrestling with them throughout the process. But I’d rather live inside those questions than settle for something clean, polished, and forgettable.

I don’t want to make films that feel like films. I want to make films that feel like memory. Like an encounter. Like you’ve seen something you weren’t supposed to, and now you can’t look away.